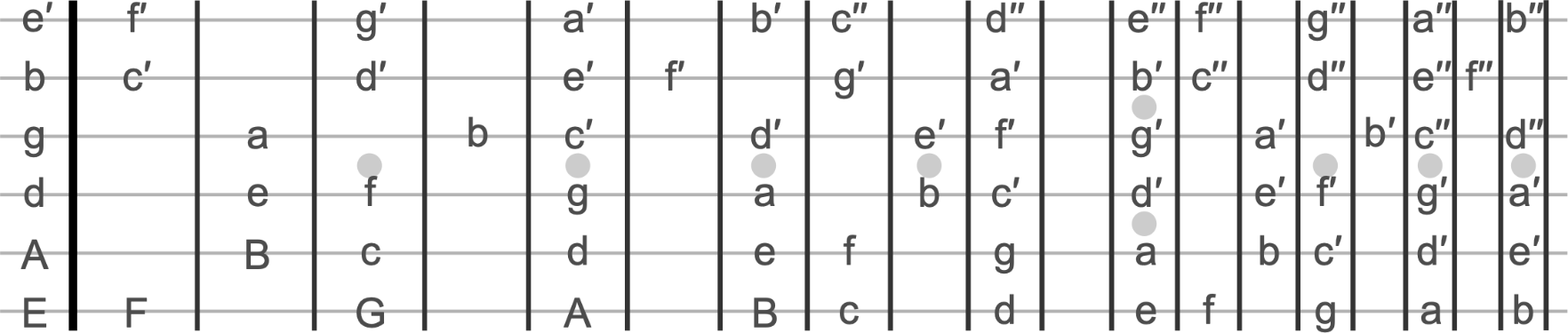

Recently I looked at the layout of the notes on the guitar fretboard, and described a useful notation for showing the absolute pitch of each note, Helmholtz pitch notation, shown here:

Perhaps one of the more puzzling things for a newcomer to music theory is the apparently uneven distribution of “natural” notes: why are they next to each other in some places like E and F, and not in others like F and G?

To understand this, we need to take a step back and look at some basic music theory.

Musical pitch and intervals

A note’s pitch is determined by the frequency it is vibrating at, and an interval describes the difference in pitch between two notes.

If two notes are vibrating at the same frequency, then the interval between them is known as unison (effectively, zero).

If one note is vibrating at twice the frequency of another, then the interval between them is called an octave.

Semitones and frets

An octave can be divided equally into twelve smaller intervals called semitones. A semitone always corresponds to one fret on the guitar.

The system of dividing every octave into twelve equal steps is called twelve-tone equal temperament.

Unless you’re dealing with microtonal music, it’s possible to describe any musical interval as a number of semitones. For example a whole tone is two semitones, which translates into two frets on the guitar.

Naturals and non-naturals

Things get more interesting when we look at how the twelve notes are named, as this does not follow a linear pattern.

Of the twelve notes within every octave, seven have their own letters: A, B, C, D, E, F and G. These notes are known as naturals.

The remaining five are described with a natural letter followed by an extra symbol. The extra symbol is either ♯ (sharp) meaning one semitone higher, or♭ (flat) meaning one semitone lower. For want of a better name, I’ll call these notes non-naturals.

Each non-natural can be described in more than one way. For example, the non-natural between C and D can be described as either as C♯ (C sharp, one semitone above C) or as D♭ (D flat, one semitone below D). Effectively, they are the same note; which name you use depends on the musical context or key you are playing in. But if you’re not playing any particular piece of music, you can use either name—it doesn’t matter.

The distribution of naturals and non-naturals

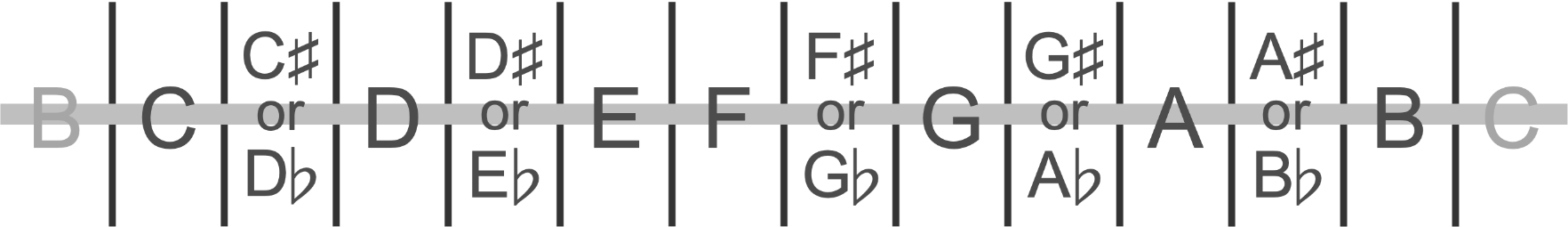

To understand how the seven naturals and five non-naturals are distributed in each octave range, look at the piano keyboard image below.

The distribution of naturals and non-naturals is shown on a piano keyboard perhaps more clearly than anywhere else, because the piano key layout corresponds exactly to the way natural and non-natural notes are laid out. Specifically, the white keys correspond to the naturals, and the black keys correspond to the non-naturals.

Even if you don’t play keyboard, it’s worth understanding this pattern, because it perfectly shows how the twelve notes are named.

To apply this pattern to a guitar string, you simply arrange these note names in a straight line, with one fret per note.

Needless to say the pattern keeps repeating at each end. On the guitar, it’s somewhat easier to see that the twelve notes are equally-spaced in terms of pitch, compared to the keyboard.

Note that there are two places within each octave range where the naturals are a semitone apart: E → F and B → C.

It’s just a naming convention

It should be emphasized, this is just a naming convention. There is nothing “special” about the natural notes compared to the others. They are just named differently. And this naming convention is universal across the many instruments and styles that use twelve-tone equal temperament.

In this musical system, a semitone is always the same interval—regardless whether you are going from a natural to a neighbouring non-natural (such as C → C♯), a non-natural to a neighbouring natural (such as C♯ → D), or a natural to another neighbouring natural (which only occurs in the two cases E → F and B → C).

Since all twelve notes within each octave are equally spaced in terms of pitch, you can play the same melody starting on any note (fret) you like. If you start on a different fret, then you’re playing the melody in a different key, but as long as all the intervals within the melody are the same—based on counting the number of semitones—then it’s the same melody.

Shifting a segment of music into a different key is called transposing.

Why are the naturals laid out like this?

The reason the natural notes are laid out in this way has to do with convention, history, and the evolution of musical traditions.

Hundreds of years ago, some styles of music used fewer than twelve notes, and the notes they did use were unevenly spaced out within an octave.

In some types of early music, just seven notes were used corresponding to what we now call naturals. Other notes were added later, bringing the total to twelve. An even later innovation was to tune the twelve notes so they are exactly equally spaced within each octave.

Because of this history and evolution, there is a deep musical significance to the way the natural notes are laid out. By transposing, the pattern of the natural notes can be applied to any musical key, and music based around this pattern is sometimes called diatonic music (regardless what key it’s in). But a closer look into that will have to wait for another time.

Visualizing the notes on the guitar fretboard

The next post in this series will provide some visualization tools to help you further understand the layout of the notes on the guitar fretboard.